Farmers Shanti and her husband Buddhman Singh, who has successfully experimented with growing capsicum using drip irrigation in open in village Bisapur Kalan in Chhindwara district of Madhya Pradesh. (Image Credit: Nivedita Khandekar)

Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana if implemented well can indeed help farmers tide over drought and major climatic changes.

Chhindwara, Madhya Pradesh: Nestled at the foothills of the Satpura ranges is the small village of Bisapur Kalan in the Chhindwara district of Madhya Pradesh. Farmer Buddhman Singh has successfully experimented with growing capsicum in the open (unlike many places that grow it in poly houses). The secret to his success? Drip irrigation.

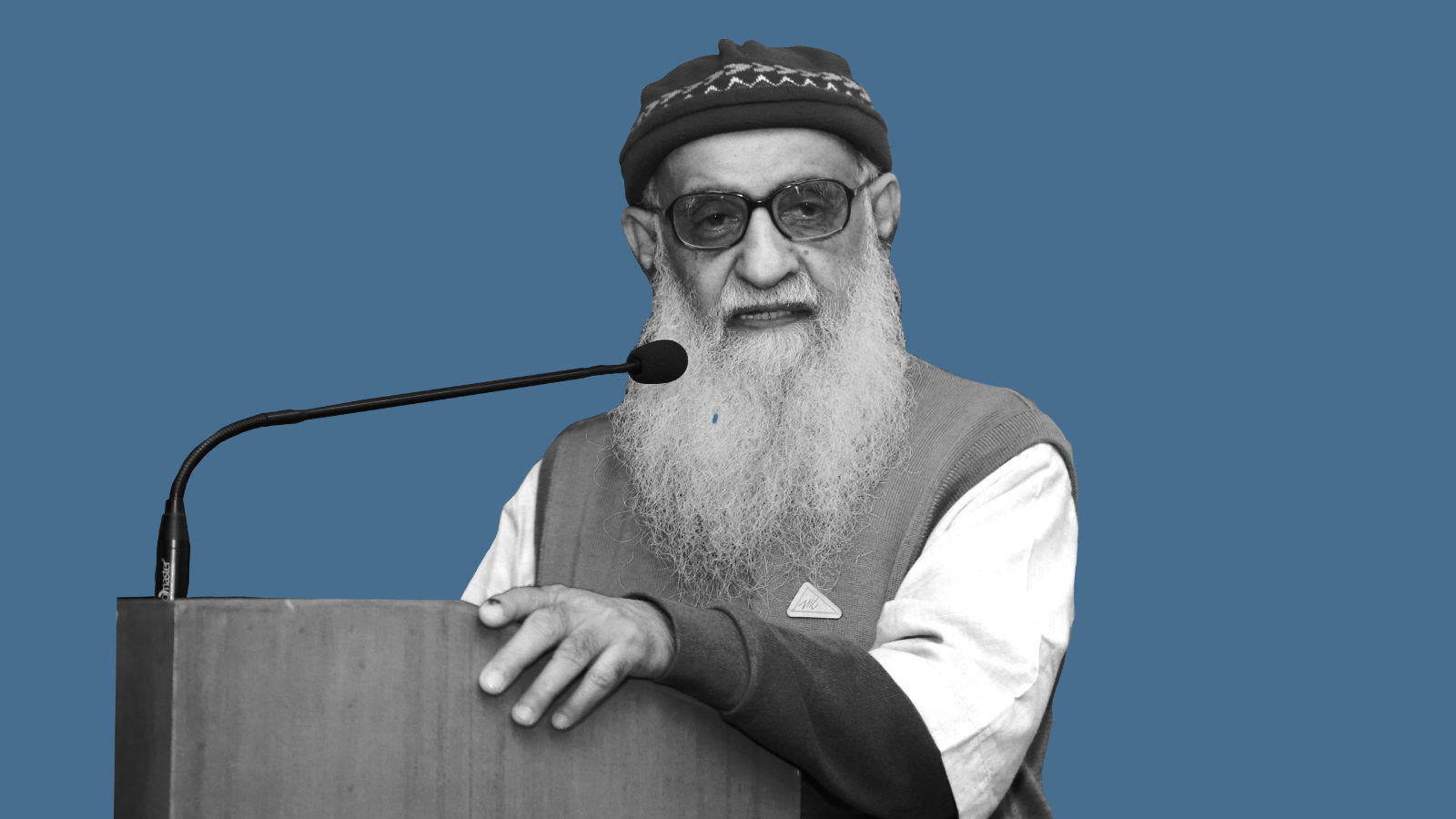

Singh has received Chief Minister’s ‘Sarvoccha Krishak Puraskar’, a cash award of Rs 50,000 and a certificate, for his innovations in the horticulture techniques in 2016. What prompted him to adopt drip irrigation system and mulching technique was the fact that it would help him grow more using less water.

Ever since Singh made the shift to horticulture — growing a variety of vegetables including capsicum on 14 acres land owned jointly by him and is wife — the couple has managed to build a pucca house and, also get a four-wheeler.

Singh did not just adopt techniques such as drip irrigation and mulching for his own farms but also encouraged several other farmers. When I met him a few weeks ago, the beaming sixty-plus farmer told me, “And why not? My income has increased now. Before I had installed drip and started using mulching, the produce would be collected in regular bamboo tokri to reach Chhindwara but now my vegetables are collected and packed neatly as I send them in trucks to different mandis across four-five states.”

Even with relatively limited water and power availability, irrigation of large farm area – almost 40 acres such as this – in Partala village of Chhindwara district is possible only because of drip irrigation. (Image Credit: Nivedita Khandekar)

These are not standalone cases. Chhindwara has seen a gradually increasing number of farmers who are taking to horticulture — some in parts, some in full — using the drip irrigation system and sprinkler system coupled with mulching. In 2016-17, more than 100 farmers, majority of them marginal, from all the blocks of the district had applied for and benefitted from the ‘More Crop Per Drop’ micro-irrigation scheme under the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY). About 350-odd farmers from across the district grow potato using drip-irrigation and get Rs 1 extra per kilogram compared to normally grown potato from a multinational company making packaged chips.

Villages such as Ridhora have taken to drip-irrigation 100 percent. Farmers in Ridhora like Jaypal Pawar and Manoj Pawar (not blood related) and many others could not stop gushing about the benefits of drip irrigation. They grew soya bean, wheat, maize and sorghum (jowar) earlier; tube wells with eight hours of water supply were able to provide limited irrigation.

With drip, the irrigated area is doubled, allowing farmers to completely shift to growing horticulture crops such as potato, tomato, chili, garlic, ginger and onions. With the water table receding to 600 feet, the situation was precarious. Many of the beneficiaries of this village for the drip/sprinkler systems are from more than five years ago.

Manoj Pawar, proudly showing off his crates of tomatoes ready to be sent to cities far away, said, “When I was young, there was nothing in our village. Today, we have education, our village has 60 tractors, many two-wheelers and even credit cards.”

It was judicious water usage with drip irrigation that transformed the situation. “Uncertain rainfall cycle leads to less and less water availability by every passing year. At the same time, agriculture input cost has been increasing but with substantially lower gains. Across all agro-climatic zones, there has been no talk ever of planned agriculture,” N S Tomar, deputy director (Horticulture), who was then in Chhindwara, told me. Tomar is now posted at Bhopal.

Indeed, rainfall has been more and more erratic. Even though Madhya Pradesh has been lucky this year, several other states are staring at severe drought situations in many of its districts. The India Meteorological Department’s (IMD) annual wrap for year 2018 drew attention to the crucial fact that though overall monsoon was 91% (south-west monsoon – June to September), it was the north-east monsoon (October-December) that had seen substantially less rainfall – 56 percent — of long period average.

On April 3, a private forecaster predicted that south-west monsoon is likely to be 93 % of the long-period average. IMD will release its forecast by mid-April. It is the south-west monsoon rainfall distribution that decides, rather dictates, the fate of India’s agriculture, which continues to primarily be rain-fed. A bountiful monsoon means proper irrigation for rain-fed crops, ground-water recharge and, also filling up of reservoirs, big and small for winter crops.

The Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation announced on April 5, that the water storage available in 91 major reservoirs of the country for the week ending on April 04, 2019 was 48.319 BCM, which is 30% of total storage capacity of these reservoirs. Scores of reservoirs, monitored by the states, have empties, almost touching dead storage, in central and peninsular India.

As per the Agriculture Census 2010-11, the net irrigated area was 64.57 million hectares, out of which 48% was accounted by small and marginal holdings; 44% by semi-medium and medium holdings and only 8% by large holdings. The same Census tells us that out of five sources of irrigation, viz. canals, tanks, wells, tube wells and other sources, it was the tube wells that emerged as the most popular source of irrigation in 2010-11 (29.16 million hectares of irrigated area) followed by canals (16.91 million hectares), wells (11.92 million hectares) and tanks (2.25 million hectares) with other sources accounting for 4.33 million hectares. Big dams and reservoirs have helped bring less than 50% of total agriculture land under assured irrigation in last six-seven decades, leaving out the rest.

And if Chhindwara farmers were to speak for the entire farming community, the water table is receding furthers still, with several blocks being already declared as dark zones.

Summer of 2019 is going to be tougher than 2016, a major drought year, for major areas in central India. Problem lies with erratic distribution of monsoon across regions and even weeks/months between June to September. Difficult years such as this one – something that India is set to witness increasingly because of changing climate – call for proper adaptation as absence of rain leads to lowered soil moisture.

It is here that the PMKSY, if implemented well, can and will help the farmers, especially small land holding farmers.

This is Part I of a two-part series on drip irrigation usage by Madhya Pradesh farmers and how drought-ridden states can make use of the method.

This write up was first published by News18 on April 10, 2019 and can be read here